Why Your BLDC Stator Runs Hotter Than the Rotor: Understanding and Managing Heat in Brushless DC Motors

You felt the stator on your brushless DC motor. Hot. The rotor? Warm at best. You are not imagining it. In most BLDC designs the stator runs hotter than the rotor and it does so for predictable physical reasons. That temperature split affects efficiency, reliability, insulation life, and magnet health. If you select laminations, size a motor, or qualify a new supplier, you need to understand what is happening and what to do about it.

This guide follows a simple expert-consultant approach. We state the problem, explain the engineering, guide you through practical options, and leave you with clear next steps. Along the way we translate jargon, highlight trade‑offs, and provide proven rules of thumb.

In This Article

- What’s Really Going On? The Engineering Fundamentals

- Primary Causes of Stator Overheating

- Why the Rotor Stays Cooler

- Consequences of Stator Overheating

- Your Options Explained: Materials, Laminations, and Manufacturing

- Which Application Is This For? Matching Choices to Use Cases

- Monitoring and Diagnosing Thermal Issues

- Your Engineering Takeaway

Part 1: The Relatable Hook — Is This Normal and What Should You Do?

You touched the frame or read a thermistor and wondered why the stator temperature sits 10°C to 50°C above the rotor. In a BLDC motor the stator houses the copper windings and the laminated iron core. That is where most electrical energy converts to torque and, unavoidably, to heat. The rotor often carries permanent magnets, not energized windings, which means less intrinsic heat generation.

So yes this is normal in principle. The real question is whether your delta and absolute temperatures are reasonable. You care because:

- Efficiency drops when copper and iron losses rise.

- Winding insulation life falls as temperatures climb.

- Magnets in the rotor can demagnetize if the stator bakes them by conduction, radiation, or heated air in the gap.

- Controllers react to changing motor constants which impacts performance.

We will unpack what drives heat in the stator vs the rotor. Then we will walk through concrete ways to reduce losses and improve heat flow.

Part 2: What’s Really Going On? The Engineering Fundamentals

Before we talk fixes, let us decode the physics. Three ideas explain almost everything: copper losses, iron losses, and heat transfer.

- Copper losses (I^2R losses). When current flows through the stator windings, resistive heating proportional to I^2 times winding resistance converts electrical power to heat. Winding resistance rises with temperature which can lead to thermal runaway if you do not control it.

- Iron or core losses in the stator. The changing magnetic field magnetizes and demagnetizes the stator core every electrical cycle. Two main contributors dominate: hysteresis losses and eddy current losses. Hysteresis relates to the area of the B-H loop and depends on material coercivity. Eddy currents are circulating currents in the laminations induced by time-varying magnetic fields. They scale with frequency and lamination thickness.

- Heat transfer. Once generated, heat must leave the windings and the laminated core. It conducts through insulation, slot liners, potting resin, and the lamination stack to the housing. It convects to internal air and the environment. It radiates across the air gap. Each step has its own thermal bottlenecks.

Think about eddy currents like tiny whirlpools in a river. A thick, solid steel core allows big whirlpools to spin and waste a lot of energy. Thin, insulated laminations break those whirlpools into many little eddies that die quickly which slashes core losses. That is why lamination thickness and insulation quality matter so much.

A few quick definitions, plain and simple:

- Flux density: how concentrated the magnetic field is inside the core. Higher flux density can yield higher torque, yet it can spike iron losses and heat if you push the core too far.

- Frequency in a BLDC: electrical frequency relates to mechanical speed and pole count. The PWM switching frequency from the inverter adds a high-frequency component that can heat copper and iron beyond what the mechanical speed suggests.

- Current density: current per cross-sectional area of the conductor. High current density can make compact stators, yet it drives high I^2R losses and heat.

Heat follows the path of least thermal resistance. Copper conducts heat well, yet it sits wrapped in enamel insulation and slot liners that do not. Laminations conduct along the sheets better than through the stack. Potting can help or hurt depending on thermal conductivity. All these elements create the stator’s thermal path impedance.

Now add power electronics to the picture. PWM drives superimpose ripple current on the phase current. High switching frequency reduces torque ripple and audible noise, yet it can increase switching losses in the inverter and skin and proximity effects in the windings. That bumps up effective AC resistance, which means more copper losses.

Part 3: Primary Causes of Stator Overheating

You know the fundamentals. Let us get specific about what makes the stator run hotter than the rotor.

A. Copper Losses (I^2R) — The Dominant Heat Generator

- Mechanism: Resistive heating in windings scales with the square of current. Doubling current quadruples I^2R losses. Winding resistance rises roughly 0.39% per °C for copper, so hot copper gets hotter faster.

- Drivers:

- Current magnitude from load and torque demand.

- Winding resistance set by wire gauge, length, and number of turns.

- Duty cycle. Continuous heavy loads push average thermal power up. Intermittent duty lets the stator cool between bursts.

- Ripple current from PWM and FOC interaction raises RMS current.

- Secondary effects:

- Skin effect and proximity effect at higher frequencies push current toward the surface of conductors and into regions close to adjacent conductors. Effective AC resistance rises which adds heating.

- Slot fill factor influences both electrical and thermal performance. Better fill can lower DC resistance which cuts I^2R, yet it can hamper cooling if you pack copper tight with poor thermal pathways.

B. Iron Losses (Core Losses) — Frequency and Flux Density Dependent

- Hysteresis losses: Energy dissipated each magnetization cycle scales with the material’s coercivity and B-H loop area. They rise with electrical frequency.

- Eddy current losses: Induced currents scale roughly with frequency squared and lamination thickness squared. Thinner laminations drop eddy losses dramatically.

- Material properties: Silicon steel grades with higher silicon content generally show reduced core losses. Grain orientation can matter in transformers. In motors you often use non-oriented electrical steel for multi-directional flux. Surface insulation between laminations stops interlaminar currents.

- Geometry and flux distribution: Tooth tips and yokes see different flux densities which can lead to localized hot spots. Air gap size and shape set flux density and harmonic content which affects iron loss.

C. High-Frequency Effects — Skin and Proximity Effects

- Where they come from: PWM switching and high electrical frequency create AC components in winding current. The skin depth in copper at tens of kilohertz gets small which drives current to the conductor surface. Nearby conductors create opposing fields that squeeze current into smaller regions.

- What to do:

- Use Litz wire for high-frequency currents. Many insulated strands keep current distributed across the conductor area which reduces AC resistance.

- Balance PWM frequency. Higher frequency can shrink torque ripple and acoustic noise. It can raise copper and inverter switching losses.

D. Inverter/PWM Ripple Current — The Indirect Amplifier

- Ripple current from the drive lifts RMS current even if average torque stays the same. RMS is what heats copper.

- Switching transitions can also inject high-frequency flux into the stator core which raises iron loss, especially if lamination thickness or material choice is not matched to the frequency content.

- Drive electronics generate their own heat as well. Motor controller thermal performance influences overall system temperatures.

E. Stator Geometry and Thermal Path Impedance

- The stator generates most of the heat and often struggles to shed it. Copper sits insulated inside slots. Heat must travel through varnish, slot liners, potting, and the lamination stack to the housing.

- Potting compounds help if they provide good thermal conductivity and fill voids. Low-conductivity resin can trap heat.

- Laminations conduct heat better along the plane than through the stack. That anisotropy can limit radial heat flow from tooth to housing. Mechanical design that improves conduction paths pays off.

Add ambient temperature to the list. High ambient reduces the temperature gradient to the environment which slows heat transfer. Motors that run fine on the bench can overheat in a sealed enclosure.

Part 4: Why the Rotor Stays Cooler

The rotor is not magic. It simply has fewer heat sources inside it.

- No current-carrying windings. The rotor in a BLDC usually only holds permanent magnets and a steel back iron. No copper in the rotor means no dominant I^2R source.

- Less hysteresis. Rotors in many BLDC designs do not cycle soft magnetic materials the same way as stators. They can use a steel sleeve or back iron, yet it sees lower dynamic magnetization compared to the stator core.

- Rotor heat sources exist yet are modest:

- Eddy current losses in magnets and sleeves grow at high speeds or with strong slot harmonics. Solid conductive sleeves can heat up. Magnet material conductivity varies which affects losses.

- Mechanical losses from air friction in the air gap and bearing friction contribute some heat. Bearings sit outside the magnet structure so heat often does not accumulate in the rotor core as quickly.

- Heat removal from the rotor can be surprisingly effective:

- Convective cooling across the air gap removes heat as the rotor spins. Spinning surfaces move air which boosts convection.

- Heat conducts along the shaft to the housing and bearings.

This does not mean the rotor is safe. If the stator runs very hot, radiation and convection can heat the rotor and magnets. Neodymium magnets can begin to lose magnetization at high temperatures depending on grade. Samarium cobalt withstands higher temperatures, yet you pay for that resilience.

Part 5: Consequences of Stator Overheating

When the stator runs too hot, you pay in several ways.

- Reduced efficiency. More input power becomes heat instead of torque. You see higher current draw for the same load which cascades into hotter copper and hotter electronics.

- Insulation breakdown. Winding insulation life roughly halves for every 10°C rise above its rated class. Class F insulation sees 155°C maximum. Class H goes to 180°C. Exceed either consistently and the motor will not last.

- Magnet demagnetization. Neodymium magnets can lose strength irreversibly if they operate above their maximum temperature. Grades vary from roughly 80°C to 180°C. Exposure to 150–200°C can cause permanent loss. Samarium cobalt tolerates roughly 250–350°C which helps in harsh environments.

- Performance drift. Winding resistance rises with temperature which changes the torque constant Kt and back-EMF constant Ke. Your control algorithm must adapt or you will see torque fall and control accuracy degrade.

- Thermal runaway. Hot windings increase resistance. Higher resistance at fixed voltage can reduce peak torque which tempts you to dial up current. More current raises I^2R loss which heats the copper further. That feedback loop can spiral.

You can avoid this with good design and thermal management.

Part 6: Your Options Explained — Materials, Laminations, and Manufacturing

This is where many teams either win or lose the heat game. The right lamination material, thickness, and stack design cut core losses and improve heat flow. The right winding and manufacturing choices drop copper losses and ease cooling. Let us walk through key decisions in two groups.

A. Material Considerations

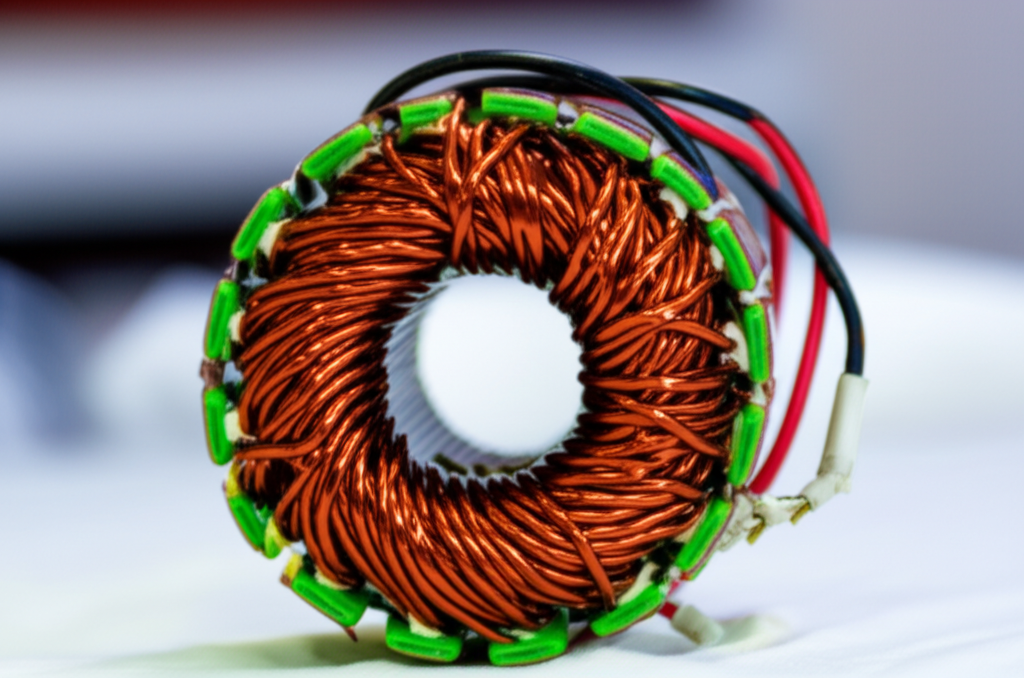

1) Electrical steel for motor cores

- Non‑oriented electrical steel is standard for motors. You choose grades for loss performance at target frequency and flux density.

- Higher silicon content generally reduces losses and increases resistivity. That lowers eddy current losses at the cost of reduced saturation flux density. There is a balance between efficiency, torque density, and material cost.

- Use reputable electrical steel laminations for predictable hysteresis and eddy performance across your operating frequency band, including PWM sidebands.

2) Lamination thickness and insulation

- Eddy currents scale with thickness squared. Moving from 0.5 mm to 0.2 mm laminations can cut eddy current loss dramatically at higher frequencies. Thinner laminations cost more and may complicate stacking and rigidity.

- Good interlaminar insulation is essential. It blocks current flow between sheets which keeps core losses low and prevents hot spots.

3) Silicon steel and advanced alloys

- Standard M‑grade motor steels cover most BLDC needs in the hundreds of hertz to low kilohertz electrical frequency range. For higher frequency or ultra‑high power density, advanced low‑loss grades and thinner gauges help.

- Cobalt‑iron alloys push saturation and reduce losses for extreme aerospace or high‑speed turbomachinery, yet they cost far more and can be harder to machine.

- For general industrial and mobility applications, modern silicon steel laminations often deliver the best cost‑to‑performance ratio.

4) Magnet materials and temperature limits

- Neodymium iron boron (NdFeB) offers high energy product which means strong torque density. It is sensitive to temperature. Choose a grade with a maximum operating temperature above your hottest realistic rotor temperature.

- Samarium cobalt (SmCo) handles heat and corrosion better though it costs more and has lower energy product.

5) Potting, varnish, and encapsulation

- Vacuum impregnation with varnish improves insulation and fills voids which improves thermal contact. It also suppresses vibration and acoustic noise.

- Potting resins vary widely in thermal conductivity. Standard resins sit around 0.2–0.5 W/mK. Thermal compounds run 1–5 W/mK. Better thermal conductivity aids heat conduction from copper to the housing.

- Potting raises thermal mass and can reduce peak temperature swings during intermittent duty, yet it can limit serviceability and add weight.

B. Manufacturing and Assembly Processes

1) Stamping vs laser cutting vs EDM

- Stamping dominates high‑volume production. It is fast and cost‑effective for repeatable geometries. It can introduce burrs and mechanical stress that you must control with good tooling and process oversight.

- Laser cutting favors prototypes and complex low‑volume shapes. Heat‑affected zones can raise local losses if parameters and post‑processing are not well controlled.

- Wire EDM yields very clean edges for demanding prototypes. It is slow and expensive for volume production.

2) Lamination stacking and bonding

- Mechanical interlocking works like LEGO bricks. It builds a rigid stack without welding which can hurt magnetic properties.

- Adhesive bonding or resin bonding improves rigidity and acoustic damping. It can enhance heat flow if you use thermally conductive adhesives and maintain good surface contact.

- Welding should be minimized on the magnetic path. Use it on outer bands or tie bars designed for that purpose.

3) Stator and rotor core construction

- The quality of your stator core lamination directly impacts hysteresis and eddy current losses at your target frequency. Good tooth geometry, fillets, and tip design reduce local flux peaks and tooth tip losses.

- Rotor back iron and sleeves handle flux return and mechanical stress at speed. Precision in the rotor core lamination stack helps maintain a uniform air gap which reduces harmonics and heat.

4) Winding choices

- Wire gauge and number of turns set resistance and inductance. Larger wire reduces DC resistance which lowers I^2R losses. It might reduce slot fill factor if you do not design the slot accordingly.

- Litz wire reduces AC resistance for high‑frequency content. It shines when PWM frequencies are high or when sensorless control injects higher harmonics.

- Series vs parallel winding schemes change current levels and copper distribution. Design for manageable current density to control copper losses and hot spots.

5) Thermal design and cooling systems

- Passive cooling

- Increase housing surface area with fins. Orientation matters because convection cares about gravity.

- Improve conduction paths from teeth to housing. Add thermal bridges or sleeves with high conductivity.

- Active cooling

- Forced air cooling can drop stator temperature by 10–30°C.

- Liquid jackets or oil cooling enable high power densities. You can see 20–50°C reductions versus forced air in many designs.

- Heat pipes move heat from the stator’s hot spots to external fins in tight spaces.

6) Controls and power electronics

- Field‑oriented control (FOC) aligns current with the rotor field which minimizes reactive currents that heat the stator without producing torque.

- Choose PWM frequency to balance switching losses and motor AC losses. Very high frequency shrinks audible noise and torque ripple. It can raise copper and iron losses and inverter switching losses. Design the system as a whole.

- Reduce DC bus ripple and voltage ripple on phases. Better filtering reduces RMS current in windings which lowers copper losses.

7) Design validation with simulation and testing

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA) for electromagnetic design predicts flux density, torque ripple, and iron losses across speed and load.

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) models convection paths inside housings and across fins which helps you tune cooling features.

- Build thermal models that include conduction, convection, and radiation. Validate them with thermocouples and embedded temperature sensors such as RTDs or NTCs.

Where do BLDC‑specific core products fit into this picture? If you build or source standardized stacks, you can accelerate development with a ready‑made BLDC stator core that balances slot design, lamination thickness, and material grade for typical electrical frequencies in BLDC drives.

Part 7: Which Application Is This For? Matching Choices to Use Cases

Different applications stress different parts of the heat equation. You do not choose the same lamination thickness or cooling for an e‑bike and a high‑speed compressor. Here is how to think about fit.

- High‑speed drones and compressors

- Electrical frequency runs high due to speed and pole count. PWM frequencies can be high to reduce noise.

- Prioritize thin laminations and low‑loss electrical steel to cut eddy current losses. Focus on precision balancing and rotor sleeves. Active cooling may be mandatory.

- Litz wire can help control AC copper losses at higher kHz switching.

- Robotics joints and cobots

- Torque at low speed with high precision. FOC runs constantly. PWM frequency often sits in mid to high kHz for smooth torque.

- Use high‑fill factor windings to minimize DC resistance. Improve conduction from teeth to housing. Consider internal fans if the joint housing allows airflow.

- Temperature sensors in the windings protect insulation and extend life.

- E‑bike and light EV traction

- Wide dynamic range with bursts of peak torque. Duty cycle varies with terrain. Ambient temperatures change outdoors.

- Optimize current density for burst performance yet keep a sane continuous rating. Forced air may not be available which makes passive cooling and housing design critical.

- Choose magnet grade for worst‑case rotor temperature under sun‑soaked frames.

- Industrial pumps and fans

- Often run near a duty point for long hours. Thermal steady state dominates.

- Size the motor so continuous losses sit within the cooling capability. Consider liquid cooling for compact high‑power density packages.

- Outer rotor vs inner rotor

- Outer rotor BLDC motors have large rotor inertia and good convective paths across the air gap. The stator sits inside which complicates heat extraction. Pay extra attention to conduction paths from stator teeth to the central hub or housing.

- Inner rotor designs mount the stator around the outside. They couple more directly to the housing which eases conduction to fins and jackets.

- Axial flux vs radial flux

- Axial flux motors often achieve high torque density with short axial length. They can concentrate flux and heat close to discs. Lamination thickness, tooth geometry, and conduction to plates matter a lot.

- Radial flux motors have long histories and many well‑understood lamination options. They offer straightforward cooling via the cylindrical housing.

If you are unsure which path suits your duty cycle and environment, compare your load profile, speed range, and ambient to your lamination and cooling options. Then run quick FEA and thermal models to narrow it down.

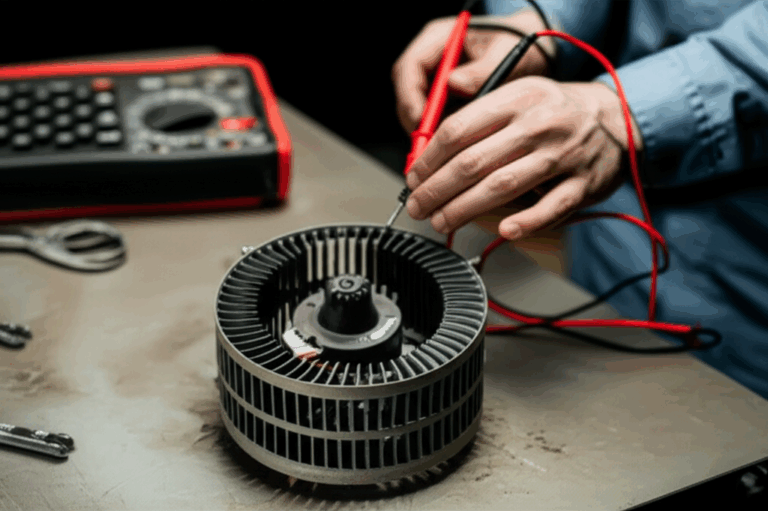

Part 8: Monitoring and Diagnosing Thermal Issues

You cannot manage what you do not measure. Simple steps prevent expensive surprises.

- Temperature sensors in windings

- Place thermistors, RTDs, or thermocouples near the hottest part of the stator. Many designers embed sensors a few millimeters into the end turns or slot liners.

- Calibrate sensor placement with thermal imaging during test runs.

- Thermal imaging and hotspots

- A quick IR scan during full‑load tests reveals uneven heating, tooth tip losses, and poor conduction zones. Look for asymmetry which hints at control or assembly issues.

- Controller telemetry

- Log RMS phase currents, DC bus voltage ripple, and switching frequency. Correlate them with stator temperature to spot thermal runaway risks under certain duty cycles.

- Bearings and shaft temperature

- Bearing temperature can spike due to over‑greasing, misalignment, or axial loads. It also provides a window into rotor heat conducted through the shaft.

- Predictive maintenance

- Trend temperature rise over ambient versus load. Rising slope over time signals insulation degradation or clogged airflow. Use that data to schedule inspections before failures hit.

- Common tests

- No‑load temperature tests isolate iron and mechanical losses. High no‑load heat hints at core loss issues or tight bearings.

- Full‑load tests validate copper loss and cooling strategy. If temperature stabilizes high, recalc continuous rating or enhance cooling.

Part 9: Putting It All Together — A Practical Troubleshooting Flow

When your stator runs hotter than you like, move through a quick checklist.

1) Verify the basics

- Check load torque and duty cycle against continuous ratings. If you run beyond continuous ratings, temperatures will rise.

- Confirm ambient temperature and ventilation. Remove obstructions to airflow.

2) Inspect control parameters

- Review PWM frequency and modulation strategy. If switching frequency is very high, try lowering it modestly or changing to space‑vector modulation to reduce harmonics in the phase currents.

- Tune FOC current loops to minimize reactive current. Ensure current sensors are accurate.

3) Measure ripple current

- Use a current probe to capture RMS current under your duty cycle. High ripple can inflate heating even if average torque stays reasonable. Improve DC bus filtering if needed.

4) Evaluate the copper path

- Check wire gauge and slot fill factor. If current density is high, consider a larger frame, thicker wire, or parallel windings.

- Move to Litz wire if switching frequency or sensorless operation creates significant high‑frequency currents.

5) Address core losses

- If no‑load heat is high, revisit lamination thickness and material. Thinner laminations and lower‑loss steel grades reduce eddy and hysteresis losses. Review tooth tip geometry if hot spots appear near teeth.

6) Improve thermal pathways

- Upgrade potting or impregnation to higher thermal conductivity compounds. Ensure complete fill without voids.

- Add heat sinks or increase fin area. Consider active cooling for high power density.

7) Reassess magnets and rotor

- For high‑speed designs, evaluate eddy loss in magnets and sleeves. Use segmented magnets, insulating sleeves, or non‑conductive retainers if eddy losses rise.

8) Validate with FEA and CFD

- Run electromagnetic FEA to confirm flux density distribution. Run CFD or thermal network models to predict temperature rise. Correlate with test data.

Part 10: Realistic Expectations and Numbers You Can Use

- Stator temperature commonly sits 10–50°C above the rotor at steady load. Larger gaps may indicate excessive stator losses or poor cooling.

- Copper losses often account for 60–85% of total motor losses in many BLDC designs. Iron losses typically run 10–30%. Mechanical and rotor losses fill the remainder.

- Every 10°C rise above insulation class rating can halve winding life. Guard your continuous rating and add overload protections.

- Thinner laminations cut eddy currents dramatically at higher electrical frequencies. Shifting from 0.5 mm to 0.2 mm can reduce eddy losses by well over half in many cases.

- Forced air cooling can drop stator temperature by 10–30°C. Liquid cooling can double that improvement for high‑power density systems.

Numbers vary with geometry, materials, and duty cycle. Use them as ballpark guidance.

Part 11: Sourcing and Specification Tips for Laminations and Cores

You do not need to reinvent cores from scratch. Mature supply chains and proven lamination stacks exist for common BLDC topologies.

- Select a partner who provides consistent steel grade certifications and stack tolerances. Electrical steel consistency drives predictable losses.

- Specify lamination thickness based on your electrical frequency spectrum which includes fundamental electrical frequency and PWM sidebands. If you plan to push switching frequency higher, update the lamination thickness accordingly.

- Validate stack bonding methods. Interlocking and adhesive bonding both work. Demand low burr height and controlled heat input during any welding on non‑magnetic paths.

- Confirm insulation class for your winding system and potting materials. Align it with worst‑case ambient and enclosure temperature.

- For an overview of complete solutions, review motor core laminations offerings to align geometry, material, and assembly with your target performance.

Frequently Overlooked Heat Contributors

- Voltage ripple and DC bus impedance. Poor bulk capacitance and layout raise phase ripple and copper heating.

- Bearing preload and alignment. Excess friction adds heat near the ends and can lift rotor temperature unexpectedly.

- Air gap eccentricity. Variations create flux harmonics which raise iron losses and noise.

- Slot harmonics from certain winding layouts. Eccentricity and slot/pole combinations can produce eddy losses in magnets and sleeves.

Part 12: Clear Answers to Common Questions

- Why is the stator hotter than the rotor in my BLDC?

- The stator contains energized windings that generate I^2R heat. It also houses the laminated core which suffers hysteresis and eddy current losses. The rotor carries magnets and back iron with less intrinsic heating.

- Is this always safe?

- Some difference is normal. It becomes unsafe if windings exceed insulation ratings or if rotor magnets approach their maximum temperature.

- Will higher PWM frequency always help?

- Not always. Higher frequency smooths torque and reduces audible noise. It can increase copper AC losses and inverter switching losses. You must balance the trade‑offs.

- Should I use Litz wire?

- Use it when high‑frequency currents cause significant AC resistance. If your switching frequency and harmonic content are low, solid or round wire may suffice.

Your Engineering Takeaway

If you remember only a few things, remember these:

- The stator runs hotter because it creates most of the losses: I^2R in copper and iron losses in the laminated core.

- Core material and lamination thickness drive iron losses which scale with frequency and thickness squared.

- PWM ripple and high‑frequency effects raise copper AC resistance which bumps heat.

- Good thermal paths and cooling matter as much as low losses. You must conduct heat out of the slots and laminations to the housing.

- Protect magnets from indirect heating. Choose grades with temperature headroom and manage the stator temperature.

- Monitor temperature with embedded sensors and IR scans. Validate with FEA and CFD.

Actionable next steps:

- Quantify temperature rise at no‑load and full‑load. Separate copper vs iron contributions.

- Revisit lamination grade and thickness if no‑load heat is high. Engage suppliers that specialize in precision stator core lamination and robust rotor core lamination stacks.

- Optimize current density and consider Litz wire if switching frequency is high.

- Improve thermal conduction paths, potting, and housing fins. Add forced air or liquid cooling if power density demands it.

- Tune control parameters. Reduce ripple current and harmonics with better filtering and modulation strategy.

- Align magnet grade with realistic maximum rotor temperature to avoid demagnetization.

You do not need to chase perfection. You do need to align materials, laminations, windings, and cooling with your duty cycle and environment. That approach delivers lower stator temperatures, better efficiency, and longer life. If you want a sanity check on material choice or lamination thickness for your target frequency band, compare options for electrical steel laminations and off‑the‑shelf BLDC stator core stacks. Then validate with quick FEA and a short thermal test on your next prototype.

When your stator stops running hot enough to make you nervous, everything else in the system gets easier. Your controller behaves. Your bearings live longer. Your magnets keep their strength. That is the payoff for doing the thermal homework today.