What Causes a Diesel Motor to Run Away? Understanding the Dangers and Prevention

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The day I met my first runaway diesel

- What “diesel runaway” really means

- The core mechanism: Why self-fueling happens

- Primary causes of diesel engine runaway

- Turbocharger failure: The leading culprit

- Fuel system malfunctions: Injectors, pumps, and governors

- External combustible sources: Vapors and fluids in the intake

- Crankcase ventilation issues: Blow-by and PCV/breathers

- ECU and sensor malfunctions: Rare, but possible

- Recognizing the signs before and during a runaway

- What to do during a diesel engine runaway (emergency actions)

- Prevention: How I safeguard engines against runaway

- Real-world consequences: Damage, cost, and risk

- FAQs I get about diesel runaway

- Final thoughts: Vigilance beats luck

Introduction: The day I met my first runaway diesel

I’ll never forget the sound. A 12-liter industrial diesel on a generator ramped from calm idle to a screaming howl in seconds. I hit the stop button. Nothing. I pulled fuel. It kept revving because it had found a new “fuel” source. Smoke poured out blue then black. A technician lunged for the emergency air intake shut-off and slammed it shut. The engine gulped. Then it died. We got lucky that day. No fire. No shrapnel. Just a hard lesson that stuck with me.

Since then I’ve seen runaway events on trucks, marine engines, heavy equipment, and generators. Different platforms. Same core mechanism. A diesel engine runs away when it starts burning fuel you didn’t intend it to burn. That can be engine oil. It can be hydraulic fluid mist. It can be flammable vapors drawn into the intake. The governor tries to cut fuel delivery yet the engine keeps feeding itself. That’s the scary part. You lose control.

In this guide I’ll walk you through what causes a diesel motor to run away, the signs to spot, what to do in the moment, and how to prevent it. I’ll share what I’ve learned in the field and why certain parts fail. My goal is simple. Keep you safe and keep your engine off the path to catastrophic failure.

What “diesel runaway” really means

When people ask me “what is diesel runaway” I say this. It’s uncontrolled engine overspeeding driven by a fuel source you don’t control. In a typical diesel you regulate speed by controlling injected fuel. You don’t throttle the air like gasoline engines do. That design works brilliantly for efficiency and durability. It also means a diesel will run on almost any combustible hydrocarbon that gets into the combustion chamber.

- No spark plugs needed. Compression ignition means hot compressed air ignites fuel.

- If oil or vapor slips into the intake manifold and reaches the cylinders you’ve got uncontrolled combustion.

- Once that feedback loop starts the engine may accelerate until it destroys itself.

That self-fueling loop is the heart of every runaway I’ve ever investigated.

The core mechanism: Why self-fueling happens

A diesel needs air, compression, and fuel. You planned to supply diesel fuel through injectors. The engine found other fuel:

- Engine oil as fuel. Oil can leak past turbocharger oil seals, flow through the intercooler, pool in the intake, and atomize into the combustion chamber. Diesels can and do burn engine oil.

- External combustible vapors. In industrial sites and refineries, engines ingest hydrocarbons floating in the air. Think propane vapors, solvent fumes, or natural gas near the intake.

- Hydraulic fluid ingestion. I’ve seen hydraulic mist from a ruptured line feed a loader’s engine like nitrous. It revved so fast the operator froze.

- Fuel system components stuck open. A stuck-open fuel injector or a failed governor can dump diesel at a rate the engine wasn’t designed to manage.

With any of those sources, the ECU or mechanical governor fights a losing battle. You cut commanded fuel yet the engine keeps self-fueling through the air path. That’s runaway.

Primary causes of diesel engine runaway

I’ve grouped the causes in the order I encounter them most often across trucks, generators, marine engines, and heavy equipment.

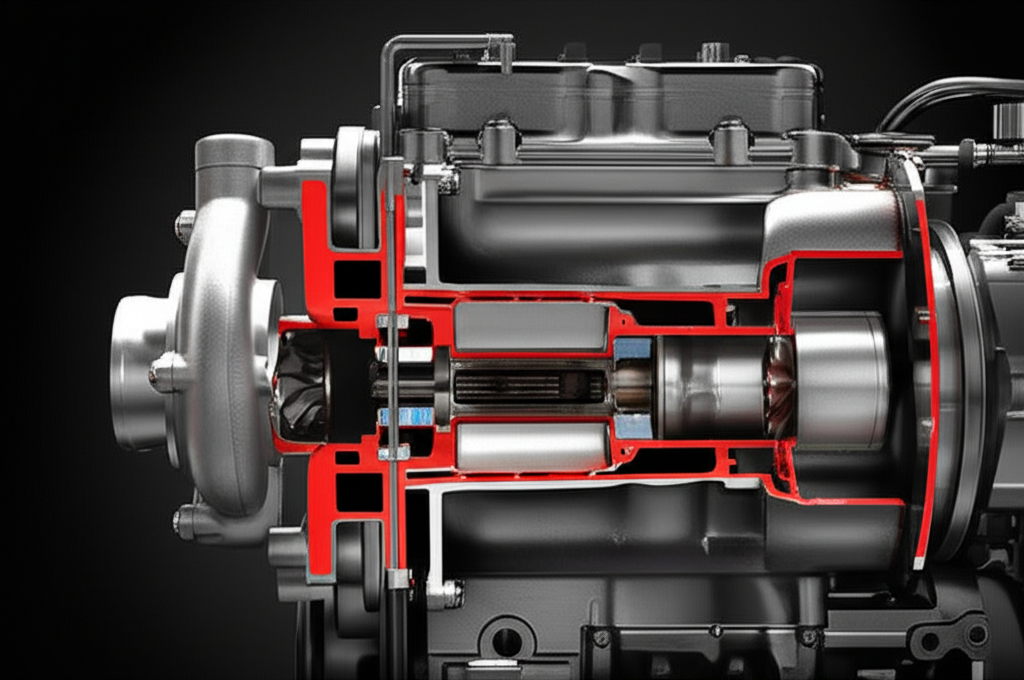

Turbocharger failure: The leading culprit

If you asked me what causes a diesel engine to run away nine times out of ten my first guess is the turbo. Turbocharger failure sits at the top of the cause list in my experience and in most service shops I’ve worked with. Here’s why.

- Worn or damaged turbo seals let oil bypass into the compressor housing. The turbocharger is fed pressurized engine oil. When bearing wear grows or seals fail oil gets pushed across into the intake.

- Oil ingestion into the intake manifold follows. Oil pools in the intercooler, saturates hoses, and gets pulled into the combustion chamber.

- High crankcase pressure from blow-by makes it worse. Worn piston rings or a clogged crankcase breather crank up pressure in the crankcase. That pressure helps push oil past turbo seals even faster.

- Oil becomes an uncontrolled fuel source. The engine starts burning its own lubricant. Overspeed begins. The louder it gets the faster it pulls in more oil mist.

What does this look like in the field? I see blue smoke first. Sometimes white smoke on cold oil. Then I hear the turbo spool harder than usual as the engine “finds” fuel. RPM spikes. If you smell burnt oil and the engine runs away you’re likely staring at a turbo seal failure.

Watch for these precursors:

- Oil in the intercooler and intake hoses

- Blue or blue-gray exhaust smoke under boost

- Sudden oil consumption with no external leaks

- Worn turbocharger bearings or compressor wheel damage

- Oil puddling in the charge pipes and intake manifold

Side note on related systems:

- A stuck exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) valve or a plugged diesel particulate filter (DPF) can create backpressure. That hurts turbo health and seals. They don’t directly cause runaway yet they can push a weak turbo over the edge.

- Variable geometry turbocharger failure can change shaft loading and oil seal conditions. Again it’s an accelerant not the root cause.

Fuel system malfunctions: Injectors, pumps, and governors

Turbo failures dominate. Fuel system failures still matter. I’ve seen stuck-open injectors flooding cylinders. I’ve seen a faulty fuel pump push rail pressure far above spec. I’ve also seen mechanical governor linkages jam in a high-fuel position.

- Stuck fuel injectors. Debris, wear, or electrical faults can hold an injector open. Fuel pours in. You get engine overspeeding and black smoke. The governor tries to rein it in yet a stuck-open injector can outpace control.

- Faulty fuel pump or rail pressure control. High-pressure pumps and pressure control valves fail. The ECU commands less yet pressure stays high and injectors over-deliver.

- Governor failure. Mechanical governors can seize or lose springs. Electronic control unit (ECU) faults can command runaway fueling at least for a moment before limp modes engage. Mechanical systems can do worse since nothing cuts them but airflow.

Do these cause runaways as often as turbo oil ingestion? Not in my world. They still show up in 15–20% of cases I’ve seen or discussed with professional diesel mechanics. When they do the smoke usually goes black not blue. The engine responds a bit to cutting the key if the injectors are still under ECU control. If the governor fails mechanically all bets are off.

External combustible sources: Vapors and fluids in the intake

If you work around refineries, chemical plants, tank farms, or sites with solvent use you must respect this one.

- Intake of flammable vapors. Diesel engines inhale air. If that air contains combustible hydrocarbons the engine treats them like fuel. Propane, methane, gasoline vapors, paint solvent fumes—any of these can feed combustion inside a hot cylinder.

- Hydraulic fluid ingestion. Heavy equipment sometimes routes hydraulic return lines near the intake snorkel. A ruptured line can atomize fluid. The engine slurps it up and accelerates.

- Other combustible liquids. I once traced a runaway to a crankcase mist heater that failed. It fed a steady stream of oil vapor into the intake tube.

In these cases the engine often refuses to shut off with the key. There’s no fuel to cut through the injectors that will stop it because it’s burning air-stream hydrocarbons. You must kill the air.

Crankcase ventilation issues: Blow-by and PCV/breathers

Diesels don’t use a gasoline PCV valve in the same way yet they need proper crankcase ventilation. Call it a breather, CCV, or separator. When it clogs or fails you get high crankcase pressure along with blow-by. That pressure forces oil past seals and into the intake.

- Clogged breather or CCV filter. I’ve pulled filters so plugged you couldn’t blow through them. The engine pushed oil past turbo seals and valve guide seals.

- Increased blow-by from ring wear. Worn piston rings and cylinder scoring raise crankcase pressure and oil mist. That oil mist heads straight for the intake if the separator fails.

- Oil in the intake manifold and intercooler. Check hoses for wetness. Pull the charge pipe off the intercooler and tilt it. If oil spills you have an ingestion risk.

I treat crankcase pressure checks as a routine diagnostic when I see oil consumption and blue smoke. It’s often the hidden accelerant behind turbo seal leaks.

ECU and sensor malfunctions: Rare, but possible

Modern diesel engines rely on sensors and an ECU for fuel control. Electronic faults usually trigger limp modes that cut power. They rarely cause mechanical runaway. I still check them because:

- A failed RPM sensor can cause late corrective action.

- A stuck EGR actuator or variable geometry vane actuator can change boost dynamics.

- A wiring harness damaged by heat or abrasion can drive bad commands.

Electronic control unit failure can dump fuel yet the ECU still controls the injectors. If you cut power or pull the fuel relay the engine usually quiets. That’s the tell. If it keeps revving after you cut fuel you’ve got external fuel and a true runaway.

Recognizing the signs before and during a runaway

Most runaways don’t come out of nowhere. Engines leave a trail of breadcrumbs. Here’s what I watch for.

Before a runaway:

- Blue smoke under boost. Oil burning points to turbo seal or valve guide issues.

- Oil consumption that feels “too high.” The dipstick moves in days not weeks.

- Oil in the intercooler and intake hoses. Pull a hose. If it’s wet you’ve got risk.

- High engine idle or hunting. The governor fights an unstable fuel/air mix.

- Whistling or howling turbo noise. Worn bearings scream before they let go.

- Check engine lights for rail pressure or injector balance. Stuck injectors often show a balance issue.

During a runaway:

- Sudden uncontrolled RPM increase. The engine revs high with no accelerator input.

- Excessive smoke. Blue smoke with oil ingestion. Black smoke with stuck injectors. Sometimes white smoke if the oil is cold or if water is present.

- Loud uncharacteristic engine noise. Knocking, rattling, and vibration can show up fast.

- Inability to shut off with the ignition key. You cut fuel. It keeps running. That’s the red flag.

If you see a mix of high RPM, blue smoke, and the engine ignoring the key you likely have oil ingestion. If you see black smoke and some response to the key suspect a fueling issue like an injector.

What to do during a diesel engine runaway (emergency actions)

I’ve trained operators and drivers on this for years. You need decisive action. You also need to keep people safe.

- Do not stand in line with the intake or the fan. Parts can fly. Flames can flash back if the intake ignites.

- Do not stare and hope it stops. It won’t. It will get louder until something fails.

What I do in order of safest effectiveness:

1) Use the installed emergency air shut-off if equipped

- Many industrial and marine diesels use an air intake shutoff valve or flap valve. It’s the best tool you’ve got. Activate it immediately. Starve the engine of air. It dies.

- Some valves are electric or spring-actuated. The actuators usually contain magnetic cores built from stacked laminations to reduce losses. If you maintain these devices the reliability stays high. If you want to understand the materials inside those actuators you can read about electrical steel laminations.

2) Block the air intake

- Use a sturdy, non-flammable object like a flat board or a thick piece of plywood. Press it firmly against the intake snorkel or the compressor inlet if you can access it safely.

- A heavy fire blanket can work. I avoid small towels that can get sucked in and shredded.

3) For manual transmissions only: stall the engine

- Engage the highest gear. Apply full brakes. Drop the clutch decisively. This is dangerous and it can damage driveline components yet it can save the engine. I reserve this for vehicles with no safe access to the intake and no air shutoff valve.

4) Avoid “brakes versus engine” on automatics

- Slamming the brakes while the engine overspeeds on an automatic transmission can cook the transmission. It often fails to stall the engine anyway.

5) Hit any emergency stop buttons

- On generators hit the e-stop. It may trip fuel and air devices. If it doesn’t and the engine keeps revving go back to step one and block the air.

6) Clear the area and call for help

- If you can’t stop it quickly or you see fire risk move people away and call emergency services.

I’ve seen people try to unplug sensors or yank battery cables. That can make it worse. It won’t stop an engine burning oil through the intake.

Prevention: How I safeguard engines against runaway

Prevention is where you win. Runaway events rarely surprise a well-maintained engine. Here’s my checklist that has paid off for years.

Turbocharger and intake care

- Inspect turbocharger bearings and seals at scheduled intervals. Watch for shaft play and oil at the compressor outlet.

- Check the intercooler and intake hoses for oil contamination. If oil drains out of the intercooler clean it properly and find the source. Do not ignore oil puddles.

- Track boost pressure. A drop in boost with rising smoke often ties back to turbo wear.

- Verify the air filter isn’t collapsing or saturated. Air intake restriction can alter turbo dynamics.

Crankcase ventilation and blow-by control

- Replace or service the crankcase breather or CCV filter on schedule. Don’t let it clog.

- Measure crankcase pressure on engines with rising oil consumption. High pressure points to ring wear or a failed separator.

- Confirm valve guide seals aren’t leaking. Oil past guides shows up on overrun and startup.

Fuel system discipline

- Keep injectors clean and tested. Balance rates that drift often warn of issues.

- Verify fuel rail pressure control works. Replace failing high-pressure pumps before they take injectors with them.

- Inspect mechanical governor linkages. Free movement is critical.

Electronics and sensors

- Check sensor harnesses for abrasion and heat damage. RPM sensors and MAP sensors keep the ECU honest.

- Make sure actuators for EGR, VGT vanes, and throttle plates move freely. Stuck actuators won’t directly cause runaway yet they can hurt turbo health.

Oil, oil level, and lubrication system

- Use the correct engine oil specifications for your platform. Diesel oils manage soot and heat. Wrong oil can coke in turbos and accelerate seal wear.

- Monitor oil consumption. If it spikes investigate immediately. Don’t just top off and forget it.

- Keep oil at the proper level. Overfilling can push oil into the intake through breathers.

Exhaust aftertreatment health

- DPF issues and exhaust brake malfunctions can raise backpressure. High backpressure punishes the turbo and seals.

- Fix an EGR cooler leak quickly. Oil and coolant contamination throws everything off.

Environment and operating practices

- In refineries or chemical plants fit engines with automatic shutdown systems designed for combustible vapors. Air intake shutoff valves save lives.

- Keep hydraulic hoses and fittings away from intake paths. Shield intakes on heavy equipment.

- Don’t park or operate near active vapor sources with the intake facing the plume.

Safety devices worth the money

- Install an air intake shutoff valve on engines working in hazardous environments. It’s the single most effective runaway prevention device.

- Consider automatic overspeed governors on mechanical engines. They act faster than a human.

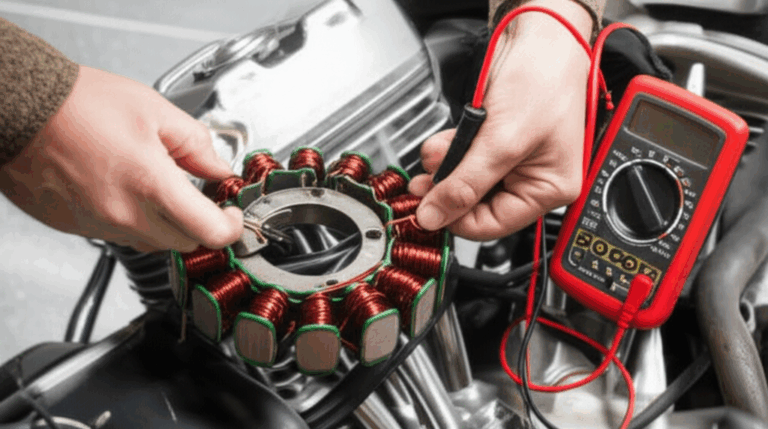

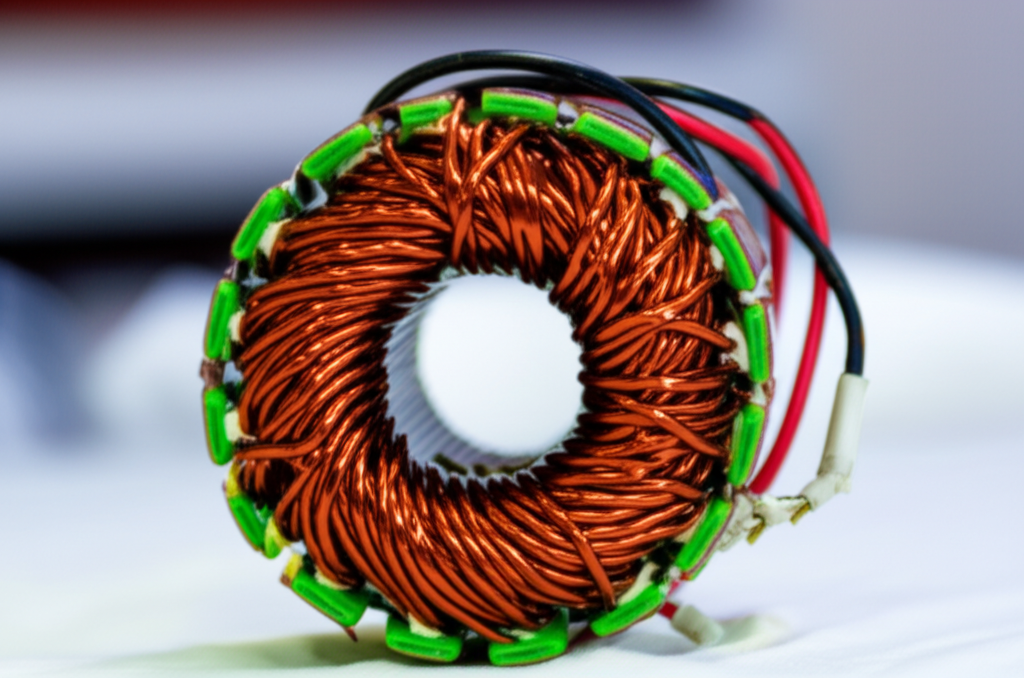

- On diesel generators I make sure the alternator and controls stay rock solid because stable control power keeps safety systems alive. The alternator itself relies on laminated iron cores to perform efficiently. If you enjoy digging into the hardware behind reliable generators you’ll like this quick overview of motor core laminations. The alternator’s stator pack is a stack of laminations too. You can learn more about the purpose and construction of a stator core lamination.

Real-world consequences: Damage, cost, and risk

People ask me if a diesel engine can survive a runaway. Sometimes it does. Often it doesn’t. Here’s what I’ve seen on teardown benches after the screaming stops.

- Pistons cracked or melted. Oil doesn’t burn clean when over-fueled. Heat skyrockets.

- Bent or broken connecting rods. Hydrolock from pooled oil can bend rods instantly.

- Spun bearings. Oil supply breaks down at extreme RPM and temperature.

- Scored cylinders and damaged valves. Debris and heat leave their mark fast.

- Turbocharger destroyed. If the seals caused it the turbo rarely survives.

- Engine block windows. In extreme cases a rod exits the block. That’s total loss territory.

Repair costs vary by engine size and application. Light-duty trucks might see $5,000–$15,000 for repairs or a swap. Heavy equipment and marine engines can blow past that range fast. Many insurers declare total losses when the block is cracked or the crankshaft is damaged beyond spec.

Risk doesn’t stop at the engine. Fire risk jumps during a runaway. Superheated oil and unburnt hydrocarbons can ignite in the engine bay. I’ve seen flames in the intake tract on shutdown. I’ve also seen intercoolers pop. You do not want to stand in front of an intake during a runaway.

FAQs I get about diesel runaway

Is turbo failure really the top cause?

- In my experience yes. Most runaways I’ve investigated tie back to turbocharger oil seal failure and oil ingestion. Industry anecdotes and shop data point the same way.

Can DPF or EGR issues directly cause runaway?

- Not directly. They raise backpressure and stress the turbo. That increases the chance of oil seal leaks which can lead to runaway. They are contributing factors not primary causes.

What color smoke shows up in a runaway?

- Blue smoke points to oil ingestion. Black smoke suggests excess diesel from injectors. White smoke can appear during cold oil ingestion or when coolant is involved. During a runaway you often see heavy blue then black as the engine chokes.

Can a diesel run on engine oil?

- Yes. That’s the root of many runaways. Engine oil becomes fuel when it atomizes in the intake stream and reaches hot compressed air in the combustion chamber.

Will cutting the key stop a runaway?

- Not if the engine is burning an external fuel source like oil mist or vapors. You must cut the air. Use an air intake shutoff valve or block the intake.

Do electronic engines run away more or less than mechanical ones?

- Less in my experience. ECUs can cut injected fuel instantly and engage safeties. Mechanical engines rely on governors that can fail. That said any diesel can run away if it finds external fuel through the intake.

Does fuel contamination cause runaway?

- Contaminated diesel can cause injector sticking or poor spray patterns. That may lead to overspeed. It’s less common than turbo oil ingestion yet it sits on my diagnostic list.

What about cold start or hot engine runaways?

- I’ve seen both. Cold start runaways often involve pooled oil in the intake overnight that gets sucked in at first crank. Hot engine runaways often follow a turbo failure after a hard pull.

Practical diagnostic checklist I use after a near-runaway

If an engine flared high and calmed down I don’t shrug. I dig. Here’s my short list.

- Pull the intake hose off the turbo compressor. Check for wet oil and shaft play.

- Disconnect the lower intercooler hose. Drain and measure oil. Any significant oil means you have a leak source.

- Run a crankcase pressure test. Compare to spec. High pressure means ring wear or a CCV issue.

- Scan for rail pressure and injector balance codes. Check commanded versus actual fuel pressure.

- Inspect the CCV filter or separator. Replace if restricted.

- Check valve guide seals if oil smoke shows up after long decel.

- Inspect EGR and DPF function. Confirm backpressure isn’t high.

- Verify the emergency air shutoff works. Test it. Tag it with the test date.

I also talk through operating conditions with the driver or operator. Did it happen under high boost. After a long idle. Near chemical vapors. Under heavy hydraulic load. Context often points me to the root cause.

Terms and concepts I explain to new techs on day one

- Diesel engine runaway causes: turbo seals, external vapors, stuck injectors, governor failure, crankcase blow-by.

- Engine overspeeding diesel and engine over-revving: the visible symptom of self-fueling.

- Oil ingestion into the combustion chamber: the mechanism behind blue smoke and runaway with turbo failures.

- Air intake restriction diesel: a stressor that hurts turbos and seals.

- Oil consumption high diesel: an early warning sign you never ignore.

- Crankcase ventilation system issues diesel: clogged breathers, CCV separators, and blow-by.

- Fuel rail pressure issues and ECU failure diesel: less common runaway triggers yet important diagnostics.

- Overspeed governor diesel and emergency shut down diesel: safety systems that save engines.

- Air intake shutoff valve and kill switch for diesel engine: your fastest route to stopping a runaway.

- Marine diesel runaway, truck diesel runaway, heavy equipment diesel runaway, generator diesel runaway: different platforms same mechanism.

- Blue smoke diesel runaway vs black smoke diesel runaway vs white smoke diesel runaway: quick clues to the fuel source.

- Preventing diesel runaway: maintenance, inspections, oil leak control, and safety devices.

I keep it simple. Understand where unwanted fuel comes from and how it reaches the cylinders. Then block those paths.

A quick note on parts quality and service discipline

I’ve turned enough wrenches to know this. Cheap seals and off-spec lubricants cost more in the long run.

- Use quality parts. Turbocharger bearings, oil seals, and injectors from reputable sources last longer and leak less.

- Use the right oil. Follow the engine oil specifications from the manufacturer. Synthetic oil can handle heat better in many applications. I still match viscosity and certifications to the engine and climate.

- Follow the service manual. The engine service manual exists to keep you out of the failure zone. Don’t skip it.

On industrial engines I also spec automatic shutdown systems when the environment demands it. They are not optional in areas with combustible vapors.

Case stories that shaped how I work

- Industrial generator runaway from turbo seal failure

We heard the RPM spike. Key off didn’t work. The air intake shutoff valve did. The post-mortem showed worn turbo bearings and oil all through the intercooler. The engine survived with new bearings, a turbo, and a full intake cleaning.

- Heavy truck with a stuck fuel injector

The driver reported sudden high idle and black smoke. He stalled the engine in fifth with a full brake stand. It saved the truck yet bent a clutch fork. The injector stuck open and the rail pressure control lagged. We replaced the injector, flushed the rail, and rechecked balance rates.

- Loader ingesting hydraulic mist

A return line cracked near the intake snorkel. Hydraulic mist fed the engine until it ran away. We blocked the intake with a board and it shut down. We rerouted hoses and added intake shielding. No repeats since.

Each case hammered home the same lesson. Air in. Fuel in. Compression. If fuel enters outside the injectors you must treat the intake as your kill switch.

Final thoughts: Vigilance beats luck

Runaway feels dramatic because it is. Yet it isn’t mysterious. The engine runs away when it finds fuel through a path you didn’t intend. Most often that path starts at a failing turbocharger. Sometimes it starts at a stuck injector or a cloud of combustible vapors. You can recognize the signs. You can stop it safely by cutting air. You can prevent it with disciplined maintenance.

If you only remember three things from me make it these:

- Blue smoke plus rising RPM often means oil ingestion. Think turbo seals and crankcase pressure.

- The key won’t stop a true runaway. The air intake will.

- An air intake shutoff valve and a clean crankcase ventilation system pay for themselves the first time they prevent disaster.

Stay vigilant. Keep your maintenance tight. Teach everyone on the team what to do in the moment. That’s how you avoid the scream you never want to hear again.