How Much Does It Cost to Replace a Stator? (Motorcycle, Car, ATV, Boat)

Table of contents

- Introduction: What I pay attention to before I quote a stator job

- What a stator does and why it matters for cost

- Average stator replacement costs at a glance

- Motorcycle stator replacement costs

- Car alternator costs (cars use alternators that contain a stator)

- ATV and UTV stator replacement costs

- Boat and marine engine stator costs

- Key factors that influence the price

- DIY stator replacement: when I do it, when I don’t

- Symptoms of a bad stator you should not ignore

- Is it worth replacing a stator

- How to cut the cost without cutting corners

- Simple diagnostics you can do before you spend money

- How long a stator lasts and what kills it

- FAQs I get all the time

- Final thoughts and next steps

Introduction: What I pay attention to before I quote a stator job

When someone asks me how much it costs to replace a stator, I don’t toss out a single number. I run through three quick checks. What vehicle are we talking about. What parts will we use. How tough is the access. That short list sets the tone for the whole estimate.

I have priced and done stator and alternator jobs for motorcycles, ATVs, boats, and plenty of cars. The spread is wide. A simple dirt bike stator swap can be a few hundred dollars. A marine outboard can run well past a thousand. Cars are different since you usually replace the whole alternator that contains the stator. I will walk you through the ranges, the parts, the labor, and the gotchas that change the final bill. I will also show you where DIY saves real money and where it can bite.

What a stator does and why it matters for cost

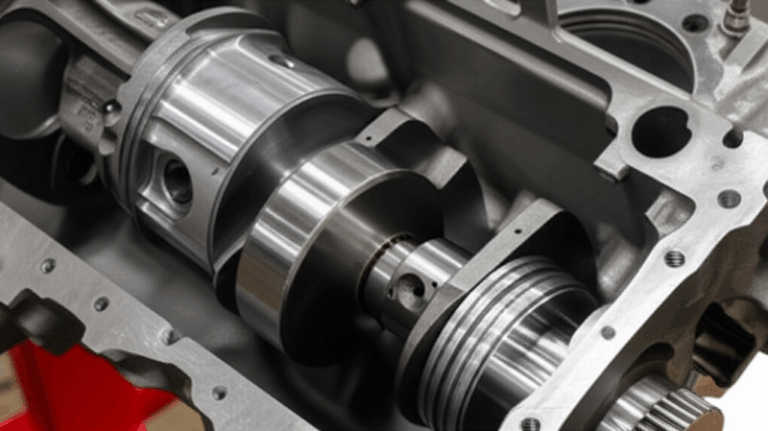

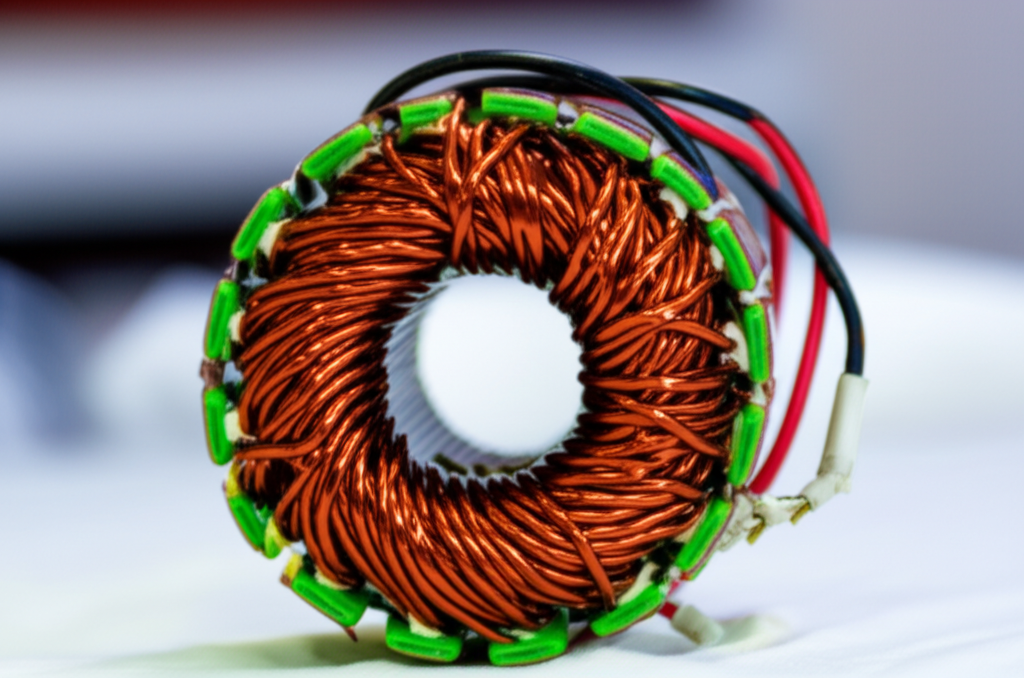

The stator sits still. The rotor spins. Together they make power for your charging system. The stator generates AC current. The regulator or rectifier converts it to DC current that charges the battery and runs your lights, ignition, and accessories.

When the stator fails, you see the fallout fast. The battery stops charging. Headlights dim. The engine stalls at idle. Sometimes you smell burnt insulation. Sometimes the main fuse blows. The failure can be a short circuit, an open circuit, or an overheating event that fries the coils. That damage drives the repair method and the parts bill.

Quality matters here. The steel stack and copper windings inside the stator form the heart of the charging system. The grade of steel and the lamination design affect heat, efficiency, and durability. If you are curious about what sits under the epoxy, the quality of the stator core lamination plays a big role in performance and price. The same goes for the rotor that spins past it. The precision of the rotor core lamination impacts energy output and noise. Manufacturers choose different lamination stacks and winding specs. That is part of why OEM parts cost more than some aftermarket options.

Average stator replacement costs at a glance

Here is the quick view I give to friends before we dig into details.

- Motorcycles

- Parts: $80 to $350 aftermarket. $150 to $600 OEM.

- Labor: $150 to $450. About 1.5 to 4 hours depending on the bike.

- Typical total: $230 to $800. Expect a bit more if you add a regulator or rectifier.

- Cars and light trucks (alternator replacement)

- Parts: $150 to $500 remanufactured or aftermarket. $250 to $800 new OEM.

- Labor: $100 to $400. About 1 to 3 hours depending on the car.

- Typical total: $250 to $900. This covers the alternator that contains the stator.

- ATVs and UTVs

- Parts: $70 to $300 aftermarket. $120 to $500 OEM.

- Labor: $120 to $350. About 1 to 3 hours.

- Typical total: $190 to $650.

- Boats and marine engines

- Parts: $100 to $600 aftermarket. $200 to $1000+ OEM.

- Labor: $200 to $800. About 2 to 5 hours with specialized marine rates.

- Typical total: $300 to $1400+. Salt and access can raise the number.

Add a diagnostic fee of $50 to $150 if the shop has not confirmed the failure. Some shops apply that fee to the repair. Some do not.

Motorcycle stator replacement costs

I see the most variation here. Sport bikes, cruisers, adventure bikes, and dirt bikes all package the stator differently. Some designs sit behind the left engine cover and bathe in oil. Others tuck deeper behind the flywheel and need more disassembly.

- Parts cost

- Aftermarket stators: $80 to $350. Brands vary on winding quality and epoxy. Warranty varies.

- OEM stators: $150 to $600. You pay for exact fit, known specs, and manufacturer warranty.

- Regulator or rectifier: $50 to $250 if you replace it as a pair. Many techs do. A weak regulator can kill a fresh stator.

- Labor hours and cost

- Most bikes take 1.5 to 4 hours. Hourly rates run $75 to $150+.

- Oil-cooled stators may need an oil change and a new gasket. Budget $10 to $30 for supplies.

- Some bikes need flywheel removal. That adds time and sometimes a special puller.

- Total range I quote

- $230 to $800 for a straight stator replacement.

- Add $50 to $250 for a regulator or rectifier plus 0.5 to 1 hour if done together.

A quick example I see often on mid-size sport bikes. A Honda CBR600RR with an aftermarket stator around $150, gasket and oil around $30, and 2.5 hours of labor at $100 per hour. Total near $430. Riders ask if they should go OEM. I weigh warranty and the bike’s use. Track days and high heat push me toward OEM. Commuting and budget lean toward a reputable aftermarket part.

Brand and model notes I run into

- Harley-Davidson often leans toward higher parts cost and longer labor. The charging system can sit behind primary covers. Plan on more oil and gasket work.

- Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki, Suzuki vary by model. Inline fours are sometimes straightforward. V-twins and adventure bikes can be trickier to access.

- Dirt bikes usually go fast and cheap. A simple side cover and a basic stator shape keep the bill down.

Car alternator costs (cars use alternators that contain a stator)

Most cars do not have a serviceable stator as a separate part. You replace the alternator as a unit. That alternator houses the stator, rotor, rectifier, and voltage regulator.

- Parts cost

- Remanufactured or aftermarket alternators: $150 to $500. You can find budget units. I avoid the rock-bottom ones due to short lifespans.

- New OEM alternators: $250 to $800. Worth it for certain vehicles that run sensitive electronics.

- Labor cost

- 1 to 3 hours in most cases. Compact engine bays on some models take longer.

- Labor runs $75 to $150+ per hour.

- Real-world range

- $250 to $900 all-in on common sedans and small SUVs.

One common example. A mid-size sedan like a Honda Civic with a reman alternator around $200 and 1.5 hours of labor at $90 per hour puts the total near $335. If the battery fought a dying alternator for months, I test it under load. Weak batteries turn a fresh alternator into a warranty claim.

ATV and UTV stator replacement costs

ATVs and UTVs act a lot like motorcycles when it comes to stators. The packaging is tight. Mud and water get everywhere. Heat cycles are tough.

- Parts cost

- $70 to $300 aftermarket. $120 to $500 OEM.

- Many owners pair the stator with a regulator or rectifier. That adds $50 to $200.

- Labor cost

- 1 to 3 hours. Rates are similar to motorcycle shops.

- Total range

- $190 to $650. Expect the high end on larger UTVs with tight engine bays and more plastic to remove.

For Polaris and Can-Am machines, I always check connectors and the wiring harness for corrosion or heat damage. A browned connector can cook a new stator. That is a cheap fix compared to a second stator job.

Boat and marine engine stator costs

Marine stators see salt, moisture, and long high-load runs. Outboards often use a stator under the flywheel. Inboards and PWC setups vary.

- Inboard vs outboard specifics

- Outboards frequently need flywheel removal and special tools. That adds labor and a bit of risk during disassembly.

- Inboards may require awkward access. Marine techs get paid for that contortion.

- Parts cost

- Aftermarket marine stators: $100 to $600.

- OEM marine stators: $200 to $1000+. Corrosion resistance and marine-grade coatings raise the price.

- Labor cost

- 2 to 5 hours. Marine hourly rates can hit $150+ due to specialization.

- Total range

- $300 to $1400+. Older outboards with seized hardware or corroded fasteners can stretch that bill.

I always remind boat owners to budget for shop supplies and possible flywheel keys, seals, or gaskets. A clean reassembly prevents repeat failures.

Key factors that influence the price

I think in buckets. Parts. Labor. Extras. Diagnostics. Each one nudges the number up or down.

- Vehicle make and model

- Accessibility is king. Easy side covers save hours. Buried stators do not.

- Specific part design, magnet strength, and winding pattern affect price.

- Part type

- OEM parts bring better warranty and predictable fit. They cost more.

- Aftermarket parts range from solid to suspect. Read reviews and check the warranty.

- Used or refurbished parts can work in a pinch. I only use them when resale value is low and the budget is tight.

- Labor rates and shop type

- Geography sets the rate. Urban shops charge more. Rural shops charge less.

- Dealerships run higher than independent mechanics.

- A seasoned technician moves faster and avoids mistakes. I do not mind paying for skill.

- Associated parts

- Regulator or rectifier. Many techs replace it with the stator.

- Gaskets, seals, and fluids. Oil-cooled stators need fresh oil and a gasket.

- Battery. A battery that suffered repeated deep discharge might be toast.

- Diagnostic time

- Expect $50 to $150 for charging system diagnosis. Good shops verify the fault before spending your money.

One more piece that affects both performance and durability. The metals used in stator and rotor stacks. If you want the nuts and bolts, look up electrical steel laminations and broader motor core laminations. Better materials reduce eddy current losses and heat. That means higher efficiency and longer life. Parts that start life with premium laminations usually cost more. They often justify it over time.

DIY stator replacement: when I do it, when I don’t

DIY saves real money. Labor is the big line item. I love a good Saturday project. I also know when I am getting in over my head.

- Pros

- You avoid $150 to $450 in labor on bikes and ATVs. More on boats.

- You learn your machine. That knowledge pays you back.

- You can choose your parts and clean connectors correctly.

- Cons

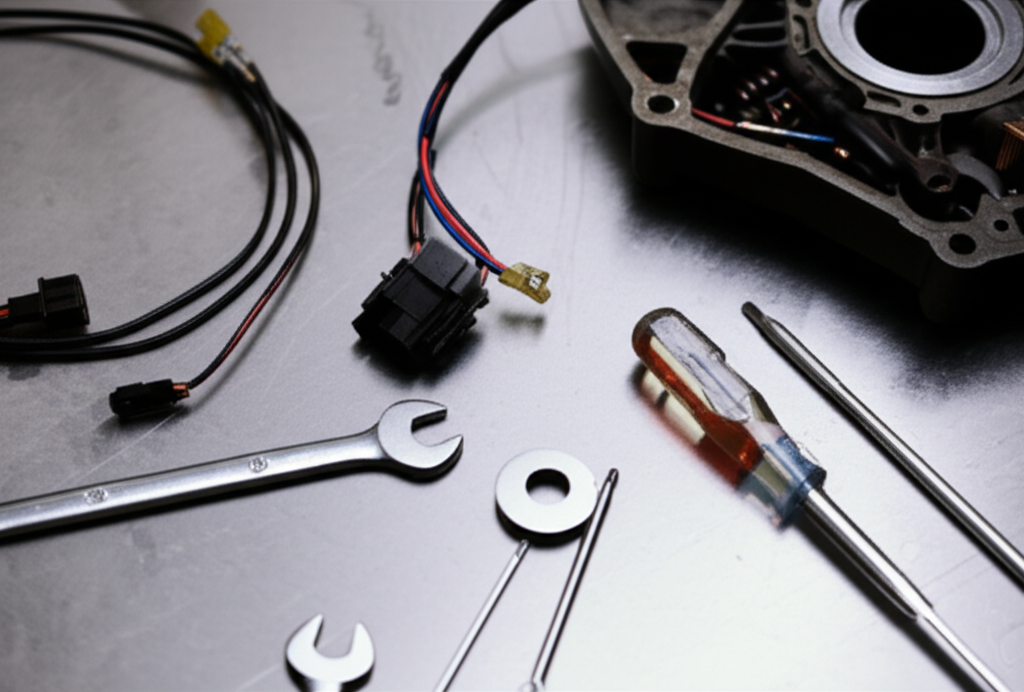

- You need tools and a service manual. A torque wrench. A multimeter. Sometimes a flywheel puller. Sometimes a gasket scraper and sealant.

- You can install it wrong. Pinched wires. Stripped cover bolts. Misrouted harnesses. Those mistakes cost time and money.

- No warranty on labor. If it fails due to install error, you own it.

- Time commitment. A pro might do it in two hours. You might take a day.

- When I go DIY

- Side-cover stators on bikes and ATVs with easy access. I grab gaskets and oil ahead of time.

- Machines with excellent service manual coverage and no specialized pullers.

- When I pay a pro

- Marine engines with heavy flywheel work. I respect the risk around keyways and torque specs.

- Tight engine bays on modern cars. The alternator might hide under three brackets and a coolant hose.

Tools I keep handy for DIY

- Multimeter for AC output and resistance checks.

- Battery charger or trickle charger to maintain the battery during diagnosis.

- Torque wrench and threadlocker for cover bolts and flywheel fasteners.

- Fresh gaskets and seals where needed.

- Service manual with torque specs and wiring diagrams.

Symptoms of a bad stator you should not ignore

I look for a cluster of clues. One symptom can come from many causes. A group of them usually points straight at the charging system.

- Dead or weak battery after a ride. It should charge while you ride. If it does not, the stator or regulator might be failing.

- Dim or flickering headlights. Especially at idle. Voltage drops mean the charging system is struggling.

- Engine stalling or misfiring at low RPM. The ignition may not get clean power.

- Charging system warning light on cars. Often a battery icon on the dash.

- Burning smell or discolored stator wires. Overheating leaves a scent and a stain.

- Blown main fuse. A shorted stator can pop it.

- Low voltage readings. You can measure DC at the battery and AC direct from the stator leads.

I confirm with a multimeter. I measure battery voltage at rest and while running. I measure AC output from the stator at idle and at a raised RPM. I check the regulator or rectifier for correct conversion. I often find the regulator has cooked the stator due to a failure to clamp voltage. That is why replacing both can be smart.

Is it worth replacing a stator

I ask three simple questions.

- What is the age and condition of the vehicle

- A healthy bike or ATV with good compression and clean wiring deserves a stator. It restores full value.

- A tired machine with multiple issues might not pencil out.

- What is the resale value

- If the repair cost exceeds a big slice of the market value, I pause. Maybe I sell as-is and disclose the issue.

- Are there cheaper alternatives

- Rewinding a stator can save money on some models. Quality varies by shop. Warranty matters.

- Used parts can bridge a gap on low-value machines. I still prefer new windings if budget allows.

For most motorcycles and ATVs, I replace the stator. The part is not expensive compared to the value of having a reliable charging system. For boats, I weigh the cost of marine-grade parts carefully. For cars, I swap the alternator and move on.

How to cut the cost without cutting corners

I like saving money. I do not like doing the same job twice. Here is how I thread that needle.

- Get multiple quotes

- Ask for a line-item breakdown. Parts, labor hours, shop supplies, and diagnostic fee. Compare apples to apples.

- Choose parts wisely

- Aftermarket can be great. Read reviews. Ask about the warranty. Confirm the output specs match OEM.

- If your machine runs sensitive electronics or you ride hot, an OEM stator or a high-output upgrade can be worth the price.

- Combine repairs

- If the regulator or rectifier is suspect, replace it with the stator. You save duplicated labor.

- Do basic diagnostics yourself

- Check battery health. Clean grounds. Inspect connectors. You might avoid paying diagnostic time for simple issues.

- Consider DIY on simple layouts

- A side cover and a gasket is an afternoon project. Take pictures as you go. Label connectors. Do not rush reassembly.

Simple diagnostics you can do before you spend money

I run this quick checklist on bikes and ATVs before ordering parts.

- Battery check

- Charge the battery fully. Test it under load. A weak battery can mimic a charging issue.

- Connector check

- Inspect the stator connector and the regulator connector. Look for burnt pins and melted housings. Clean and repair as needed.

- Resistance check

- With the engine off, disconnect the stator. Measure resistance between stator leads. Compare to the service manual.

- Check resistance to ground. It should be open. If not, the stator is shorted.

- AC output check

- With the engine running, measure AC voltage between stator leads. It should rise with RPM. No rise means no output.

- DC charging check

- Measure battery voltage at idle and at 3,000 RPM. You should see roughly 13.5 to 14.5 volts on many bikes. Numbers outside that range point to stator or regulator issues.

This quick process saves time and money. It also helps you speak the same language as the mechanic when you get quotes.

How long a stator lasts and what kills it

I have seen stators last for tens of thousands of miles. I have also seen new ones cook in a season. What makes the difference.

- Heat and airflow

- Stators that sit in oil usually handle heat better. Air-cooled designs can run hot at low speed. Heat ages insulation and breaks down epoxy.

- Electrical overloads

- High-draw accessories stress the charging system. Heated gear and extra lights add up.

- Bad regulator or rectifier

- A faulty R/R can overcharge or undercharge. Both conditions are hard on the stator.

- Manufacturing quality

- Windings, epoxy, and steel laminations matter. Higher quality materials resist heat and vibration better. If you care about the material side, the structure of the lamination stack inside the stator and rotor is central. You can dig deeper into that with the stator core lamination resource I shared earlier.

- Corrosion and moisture

- Boats and wet off-road use accelerate corrosion. Seals and connectors must stay healthy.

If you want a mental model, think of the charging system as a small power plant. Copper makes power. Steel guides the magnetic path. Better steel with the right silicon content reduces losses. That is why you see manufacturers talk about their lamination stacks. Those stacks are not random. They are engineered for performance and longevity.

FAQs I get all the time

- Can I drive or ride with a bad stator

- Not for long. You will drain the battery. The engine will stall. You might get stranded.

- How much labor for a motorcycle stator

- Most jobs land between 1.5 and 4 hours. Some Harleys and adventure bikes take longer.

- Is it worth replacing the regulator or rectifier with the stator

- Usually yes. A weak regulator can fry a new stator. The part is not expensive compared to doing the job twice.

- Is rewinding a stator a good idea

- It can be. Quality depends on the shop. Ask about materials, output specs, and warranty.

- Do I need a diagnostic before replacement

- I recommend it. A $50 to $150 diagnostic can save a $300 mistake.

- What tools do I need for DIY

- A service manual. A multimeter. Basic sockets and screwdrivers. A torque wrench. Sometimes a flywheel puller and a gasket scraper.

- Will a high-output stator help

- If you run accessories that overload the stock system, a high-output upgrade can help. It may run hotter. Make sure the regulator and wiring can handle the load.

Final thoughts and next steps

You asked about money. Here is the bottom line again.

- Motorcycles: $230 to $800 for stator replacement. Add $50 to $250 if you pair the regulator.

- Cars: $250 to $900 for alternator replacement.

- ATVs and UTVs: $190 to $650 for stator replacement.

- Boats: $300 to $1400+ for stator work on marine engines.

Get two or three quotes. Ask for parts and labor broken out. Verify the diagnostic. Decide on OEM or aftermarket based on warranty, output, and your use case. Do not forget the hidden costs like gaskets, fluids, shop supplies, and possible wiring repairs.

If you want to understand why some parts cost more and last longer, the materials behind them are a big reason. The lamination stacks and steel grade change efficiency and heat. If you like that technical rabbit hole, skim what goes into electrical steel laminations and wider motor core laminations. The same logic applies to the spinning side with rotor core lamination.

Pick your path. DIY makes sense on simple layouts with clear manuals. A pro saves headaches on complex setups or marine jobs. Either way, you will avoid surprises now that you know the parts, labor, and the factors that push the price up or down.